Why is understanding money and credit central to understand the world order?

Because what most people and their countries want the most is wealth and power, and because money and credit are the biggest single influence on how wealth and power rise and decline, if you don’t understand how money and credit work, you can’t understand the biggest driver of politics within and between countries so you can’t understand how the world order works. And if you don’t understand how the world order works, you can’t understand what’s coming at you.

The two major dynamics in the world

1) how money, credit, and economics work

2) how domestic and international politics work

How does one go broke?

When one’s income is less than one’s expenses and one’s assets are less than one’s liabilities (i.e., debts), one is on the way to having one’s assets sold and going broke.

Current state of things

As for what is happening now, the biggest problem that we collectively now have is that for many people, companies, nonprofit organizations, and governments the incomes are low in relation to the expenses, and the debts and other liabilities (such as those for pension, healthcare, and insurance) are very large relative to the value of their assets. It may not seem that way—in fact it often seems the opposite—because there are many people, companies, nonprofit organizations, and governments that look rich even while they are in the process of going broke. They look rich because they spend a lot, have plenty of assets, and even have plenty of cash. However, if you look carefully you will be able to identify those who look rich but are in financial trouble because they have incomes that are below their expenses and/or liabilities that are greater than their assets so, if you project out what will likely happen to their finances, you will see that they will have to cut their expenses and sell their assets in painful ways that will leave them broke.

What does it mean for a currency to be the global reserve reserve currency?

Having a reserve currency is great while it lasts because it gives the country exceptional borrowing and spending power but also sows the seeds of it ceasing to be a reserve currency, which is a terrible loss. That is because having a reserve currency allows the country to borrow a lot more than it could otherwise borrow which leads it to have too much debt that can’t be paid back which requires its central bank to create a lot of money and credit which devalues the currency so nobody wants to hold the reserve currency as a storehold of wealth.

As a result of having the ability to print the world’s currency the United States’ relative financial economic power is multiple times the size of its real economic power.

Two intertwined but different economies

[To] understand what is likely to happen financially and economically one has to watch movements in the supplies and demands of both the real economy and the financial economy.

When does the ability of central banks to be stimulative end?

[The] ability of central banks to be stimulative ends when the central bank loses its ability to produce money and credit growth that pass through the economic system to produce real economic growth. That lost ability of central bankers typically takes place when debt levels are high, interest rates can’t be adequately lowered, and the creation of money and credit increases financial asset prices more than it increases actual economic activity. At such times those who are holding the debt (which is someone else’s promise to give them currency) typically want to exchange the currency debt they are holding for other storeholds of wealth. When it is widely perceived that the money and the debt assets that are promises to receive money are not good storeholds of wealth, the long-term debt cycle is at its end, and a restructuring of the monetary system has to occur. In other words the long-term debt cycle runs from 1) low debt and debt burdens (which gives those who control money and credit growth plenty of capacity to create debt and with it to create buying power for borrowers and a high likelihood that the lender who is holding debt assets will get repaid with good real returns) to 2) high debt and debt burdens with little capacity to create buying power for borrowers and a low likelihood that the lender will be repaid with good returns. At the end of the long-term debt cycle there is essentially no more stimulant in the bottle (i.e., no more ability of central bankers to extend the debt cycle) so there needs to be a debt restructuring or debt devaluation to reduce the debt burdens and start this cycle over again.

How do stocks respond to a currency devaluation?

That shift from a) a system in which the debt notes are convertible to a tangible asset (e.g., gold) at a fixed rate to b) a fiat monetary system in which there is no such convertibility last happened in 1971. When that happened—on the evening of August 15, when President Nixon spoke to the nation and told the world that the dollar would no longer be tied to gold—I watched that on TV and thought, “Oh my God, the monetary system as we know it is ending,” and it was. I was clerking on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange at the time, and that Monday morning I went on the floor expecting pandemonium with stocks falling and found pandemonium with stocks rising. Because I had never seen a devaluation before I didn’t understand how they worked. Then I looked into history and found that on Sunday evening March 5, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt gave essentially the same speech doing essentially the same thing which yielded essentially the same result over the following months (a devaluation, a big stock market rally, and big gains in the gold price), and I saw that that happened many times before in many countries, including essentially the same proclamations by the heads of state.

How do central banks respond when the credit cycle reaches its limit?

When credit cycles reach their limit it is both the logical and the classic response for central governments and their central banks to create a lot of debt and print money that will be spent on goods, services, and investment assets to keep the economy moving. That is what was done during the 2008 debt crisis, when interest rates could no longer be lowered because they had already hit 0%. As explained that was also done in response to the 1929-32 debt crisis, when interest rates had been driven to 0%. This creating of the debt and money is now happening in amounts that are greater than at any time since World War II.

Is it wise to rely on government to protect us financially?

History has shown us that we shouldn’t rely on governments to protect us financially. On the contrary, we should expect most governments to abuse their privileged positions as the creators and users of money and credit for the same reasons that you might do these abuses if you were in their shoes. That is because no one policy maker owns the whole cycle. Each one comes in at one or another part of it and does what is in their interest to do at that time given their circumstances at the time.

How do governments react when they have power over money?

[In] virtually all cases the government contributes to the accumulation of debt in its actions and by becoming a large debtor and, when the debt bubble bursts, bails itself and others out by printing money and devaluing it. The larger the debt crisis, the more that is true. While undesirable, it is understandable why this happens.

How do governments react when they have debt problems? They do what any practical, heavily indebted entity with promises to give money that they can print would do. Without exception, they print money and devalue it if the debt is in their own currency.

How do people respond when they realize what’s happening?

When this happens enough that the holders of this money and debt assets realize what is happening, they seek to sell their debt assets and/or borrow money to get into debt that they can pay back with cheap money. They also often move their wealth to other storeholds of wealth like gold, certain types of stocks, and/or somewhere else (like another country that is not having these problems). At such times central banks have typically continued to print money and buy debt directly or indirectly (e.g., by having banks do the buying for them) and have outlawed the flow of money into inflation-hedge assets and alternative currencies and alternative places.

[People] flee out of both the currency and the debt (e.g., bonds). They need to decide what alternative storehold of wealth they will use. History teaches us that they typically turn to gold, other currencies, assets in other countries not having these problems, and stocks that retain their real value.

Typically at this stage in the debt cycle there is also economic stress caused by large wealth and values gaps, which lead to higher taxes and fighting between the rich and the poor, which also makes those with wealth want to move to hard assets and other currencies and other countries. Naturally those who are governing the countries that are suffering from this flight from their debt, their currency, and their country want to stop it.

So, at such times, governments make it harder to invest in assets like gold (e.g., via outlawing gold transactions and ownership), foreign currencies (via eliminating the ability to transact in them), and foreign countries (via establishing foreign exchange controls to prevent the money from leaving the country).

What happens in the late stages of the long-term debt cycle?

[Later] in the long-term debt cycle when the amounts of debt are large and when there isn’t much room to stimulate by lowering interest rates (or printing money and buying financial assets) the greater the likelihood that there will be a monetary inflation accompanied by economic weakness.

When this becomes extreme so that the money and credit system breaks down and debts have been devalued and/or defaulted on, necessity generally compels governments to go back to some form of hard currency to rebuild people’s faith in the value of money as a storehold of wealth so that credit growth can resume.

Do people see the blowup coming?

Because most people don’t pay attention to this cycle much in relation to what they are experiencing, ironically the closer people are to the blowup the safer they tend to feel. That is because they have held the debt and enjoyed the rewards of doing that and the longer it has been from the time since the last one blew up, the more comfortable they have become as the memories of the last blowup fade—even as the risks of holding this debt rise and the rewards of holding it decline.

[That] big blowup (i.e., big default or big devaluation) happens something like once every 50 to 75 years.

These cycles of debt and writing off debts have existed for thousands of years and in some cases have been institutionalized. For example, the Old Testament provided for a year of Jubilee every 50 years, in which debts were forgiven (Leviticus 25:8-13).

History of US monetary system, 1945-present

I haven't provided any excerpts under this subheading. Instead, please refer to the original text. It’s long. Its title is, “The Monetary System That We Are in, from Its Beginning until Now.” Please use either of these links to access Chapter 2: link 1, link 2.

Three types of expansionary monetary policy

Monetary Policy 1: the lowering of interest rates. It is the first-choice monetary policy.

Monetary Policy 2: the printing of money and the buying of financial assets, mostly government bonds and some high-quality debt.

The last time they had needed to do that because interest rates had hit 0% began in 1933 and continued through the war years. This approach is called “quantitative easing” rather than “debt monetization” because it sounds less threatening. All the world’s major reserve currency central banks did this [starting in 2008].

Monetary Policy 3: works by the reserve currency central governments increasing their borrowing and targeting their spending and lending to where they want it to go with the reserve currency central banks creating money and credit and buying debt (and possibly other assets, like stocks) to fund these purchases. [Doesn’t sound much different from MP2 ... What’s the difference?]

Throughout all this time [during the long-term debt cycle], inclusive of all of these swings, the amount of dollar-denominated money, credit, and debt in the world and the amounts of other non-debt liabilities (such as pensions and healthcare) continued to rise in relation to incomes, especially in the US because of the Federal Reserve’s unique ability to support this debt growth.

So, before we had the pandemic-induced downturn, the circumstances were set up for this path being the necessary one in the event of a downturn.

What is the significance of April 9, 2020?

The coronavirus trigged economic and market downturns around the world, which created holes in incomes and balance sheets, especially for indebted entities that had incomes that suffered from the downturn. Classically, central governments and central banks had to create money and credit to get it to those entities they wanted to save that financially wouldn’t have survived without that money and credit. So, on April 9, 2020 the US central bank (the Fed) announced a massive money and credit creation program, alongside massive programs from the US central government (the president and Congress). They included all the classic MP3 techniques, including helicopter money (direct payments from the government to citizens). It was essentially the same announcement that Roosevelt made on March 5, 1933.

What fraction of international transactions are in dollars?

The US dollar now accounts for about 55% of the world’s international transactions, savings, and borrowing. The Eurozone’s euro accounts for about 25%. The Japanese yen accounts for less than 10%. The Chinese renminbi accounts for about 2%.

[The dollar amount of global trade is around $25 trillion per year, as of April 2019. This is across all currencies; source. In contrast, global GDP is $87 trillion in nominal terms, as of 2019; source 1, source 2]

How much dollar-denominated debt is there outside the US?

Dollar-denominated debt owed by non-Americans (i.e., those in emerging markets, European countries, and China) is about $20 trillion (which is about 50% higher than what it was in 2008), with a bit less than half of that total being short-term.

These dollar debtors will have to come up with dollars to service these debts and they will have to come up with more dollars to buy goods and services in world markets.

The World Order Cycle

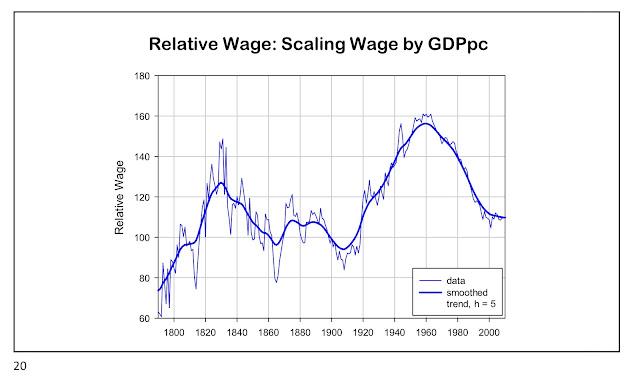

Stepping back to look at all of this from the big-picture level, what I’m saying about the relationship between 1) the economic part (i.e., money, credit, debt, economic activity, and wealth) and 2) the political part (both within countries and between countries) of rises and declines looks like the picture shown below. Typically the big cycles start with a new world order—i.e., a new way of operating both domestically and internationally that includes a new monetary system and new political systems. The last one began in 1945. Because at such times, after the conflicts, there are dominant powers that no one wants to fight and people are tired of fighting, there is a peaceful rebuilding and increasing prosperity that is supported by a credit expansion that is sustainable. It is sustainable because income growth exceeds or keeps pace with the debt-service payments that are required to service the growing debt and because of central banks’ capacities to stimulate credit and economic growth is great. Along the way up there are short-term debt and economic cycles that we call recessions and expansions. With time investors extrapolate past gains into the future and borrow money to bet on them continuing to happen, which creates debt bubbles at the same time as the wealth gaps grow because some benefit more than others from this money-making upswing. This continues until central banks run out of their abilities to stimulate credit and economic growth effectively. As money becomes tighter the debt bubble bursts and credit contracts and with it the economy contracts. At the same time, when there is a large wealth gap, big debt problems, and an economic contraction, there is often fighting within countries and between countries over wealth and power. These typically lead to revolutions and wars that can be either peaceful or violent. At such times of debt and economic problems central governments and central banks typically create money and credit to fund their domestic and war-related financial needs. These money and credit crises, revolutions, and wars lead to restructurings of a) the debts, b) the monetary system, c) the domestic order, and d) the international order — which together I am simply calling the world order.

[Note: I don’t believe the x-axis has been drawn to scale in the sense that the time from the start of the latest New World Order (1945) to the present time (represented by the peak in the above chart) is probably much longer than the time from the present until the NEXT New World Order. I’m guessing that it will be probably another 10 years. Maybe 25 years.]

Next question: Why and how all currencies devalue and/or die? Answer is forthcoming.